(UPDATED) KDP Select is a promotional tool within Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing program. It’s optional, but for those who do opt-in to KDP Select, it offers several benefits to self-published authors.

The biggest: the ability to create “free” promotions for self-published books (in my experience, 5 “free” days per quarter), which leads to higher ranking within Amazon’s categories, which in turn results in more prominence across Amazon.com and (theoretically) more sales. There are some other benefits, including higher royalty rates in secondary markets, small payments for “borrows” on the Kindle, and the Amazon Countdown program.

But there’s a catch: KDP Select requires participating authors to promise not to distribute their work on other platforms, such as Apple’s iBookstore or Google Play.

While many authors will say, “So what? I hardly sell any ebooks for the iBookstore/Nook/Google Play/etc.,” giving in to KDP Select supports Amazon’s monopolistic ambitions by removing content from competing platforms. In this post, I’ll talk about KDP Select and why I believe it is ultimately bad for authors.

If you sign up for KDP to self-publish your books, it’s easy to be tricked into signing up for KDP Select, owing to prominent, cleverly worded sign-up forms that litter the KDP interface. But remember that it’s optional. If you join KDP, you don’t need to sign up for KDP Select. Indeed, I urge you not to sign up, for the following reasons:

- Sales from KDP Select promotions may be limited. While some authors have great results from KDP Select, others don’t see much in terms of increased sales or rankings. I experimented quite a bit with Select in 2013 and experienced paltry sales and reimbursements. The rankings boost was negligible. I stopped using KDP Select in mid–2013, and haven’t looked back (sales have actually been stronger than ever across multiple platforms in the past few months).

- KDP Select reduces the number of readers you can reach with your books. I want to make my titles available to as wide an audience as possible, and KDP Select runs counter to that. It actually aims to establish a monopoly over reader eyeballs and self-publishing authors. It’s not only a poor way to treat readers who want to buy from other platforms and use other devices, but also limits our options down the road when competing platforms wither and fail.

On this last point, ask yourself what incentives there are for Amazon to improve the KDP UI, payouts, and policies for self-published authors if there is no credible competition. Nook is already failing (YOY sales are down 50% for me), Apple is so slow to implement change, and Google has only recently begun to improve Google Play for books.

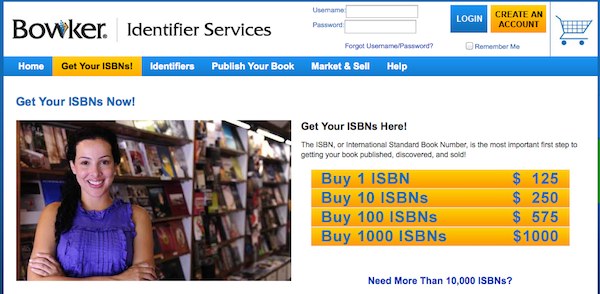

Locking content out of these platforms via KDP Select or any other similar scheme will hasten their decline or stifle their growth, and ultimately hurt us in the long run. Competition leads to better interfaces for readers and authors, higher revenue-shares, and policies that deliver value for readers and writers alike. If Amazon is the only player in town, they don’t need to pay attention to anyone’s needs, and indeed can exploit the situation for the benefit of their owners and shareholders (which we’ve seen in the publishing industry in the past; see Bowker’s 12,500% ISBN markup for new authors.)

Bottom line: KDP Select is great for Amazon’s long-term strategic goals of dominating the publishing industry. It may even help some authors juice sales of certain titles. But ultimately it will erode the viability of other platforms, which is not good for us or readers.

UPDATE: In July 2014, Amazon launched its Kindle Unlimited subscription program. Most KDP Select titles were apparently automatically enrolled. I have evaluated the subscription program’s payouts for self-published authors, and have concluded that it treats self-published authors unfairly and is likely to cannibalize full-priced digital downloads. See Amazon’s Kindle Unlimited subscription plan screws self-published authors for details.